would you be/go mad if i haunted the narrative with my absence?

comparing the role of imagination in rebecca (1940) and rebecca (2020)

This Halloween I want to invite you to come back to Manderley with me… I am taking a closer look at the two film adaptations of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, a gothic romance with spooky vibes. This article is based on an essay I wrote for school so it’s a little longer than usual, but I hope you like it nevertheless!

“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again…”

What’s in a name? In Daphne du Maurier’s novel, everything is in the name Rebecca. The character haunts the novel with her presence, even though the story only starts after she has died. Still, her influence remains in the life of her husband Maxim de Winter and the new Mrs. De Winter, who tells the story. She is also never absent from the viewer’s imagination.

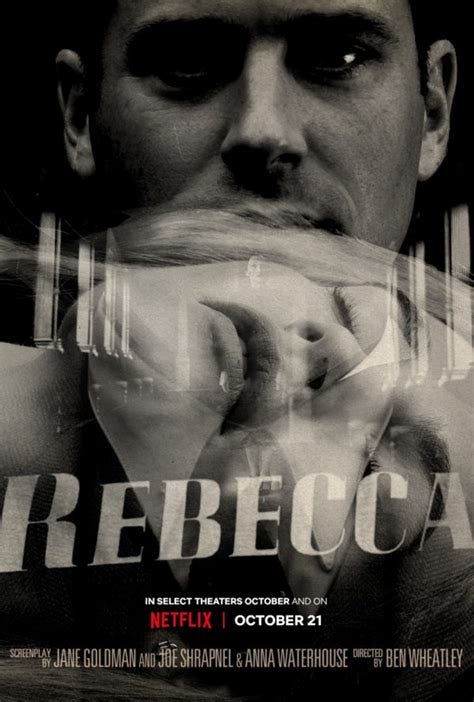

The story inspired Alfred Hitchcock to adapt it in 1940, and eighty years later, Ben Wheatley brought another adaptation to the silver screen.

The 2020 adaptation of Rebecca takes an explicit approach to the “re-imagining” of Rebecca, both from an adaptive and imaginative point of view. Rebecca looms quite literally through the halls of Manderley in a red dress and with her long, dark hair. The film “switches to the showing mode, silencing the voice of the character” when Mrs. De Winter (Lily James) conjures up an image of Rebecca.1 This leads to a different way and experience of building up the viewer’s idea of the unseen character Rebecca.

Here, it is thus Mrs. De Winter who imagines Rebecca. In doing so, her imagination is visualized on the screen. This same visualization is taken on by us, and we keep relying on this image when Rebecca is not seen but still present, for example when they talk about her. The visualized imaginative depiction of Rebecca becomes part of the viewer’s “schemata” (information with which we understand the narrative).2

As we see Rebecca moving through Manderley, there is no longer the need to imagine her, since we can perceive her onscreen. Her visualization interrupts the imaginative process and replaces our imaginative visualization of her.

In some scenes, the appeal to the imagination takes a similar shape in the two adaptations. In the scene depicted in the frames above, housekeeper Mrs. Danvers leads Mrs. De Winter through Rebecca’s old rooms in the West Wing. Here, she shows Mrs. De Winter how she used to do their nightly routine and places her in the spot where Rebecca used to sit. Brushing her hair like she used to brush Rebecca’s long, dark hair after Rebecca would say “Come on, Danny! Hair drill!” These words are spoken to suggest Rebecca saying them by mimicking Rebecca’s tone and voice, allowing us to engage our imagination. Mrs. De Winter functions, in both films, as a stand-in for Rebecca as she is placed in front of the mirror whilst Mrs. Danvers brushes her hair.

A similar appeal to our imagination is made when Mrs. De Winter arrives at the ball. She is wearing the same costume Rebecca wore to the ball a year earlier, inspired by one of the paintings on the gallery wall. The spectator only knows this after seeing Maxim’s reaction in the 2020 version and when his sister whispers the name “Rebecca” as if she has seen a ghost in the 1940 adaptation. This way, we might imagine Rebecca in Joan Fontaine’s dress, with long, dark hair, beaming with confidence (as opposed to the new Mrs. De Winter). We are engaged to picture the ball of a year ago, seeing Mrs. De Winter as Rebecca to construct our imagination of the year before.

In the 2020 adaptation, the addition of the dark wig and the red dress almost do not need us to imagine. It can immediately be connected to and united with our earlier perception of Rebecca in the red dress, which was seen in Mrs. De Winter’s dreams. The appeal to the imagination is thus less strong, and here it is perception that helps us reconstruct the past.

Movies are often deemed “less powerful” or leave less to the imagination compared to a written work. This seems to be the case in the 2020 film. Still, this doesn’t have to be true for every film: Film can engage the imagination, it just has the option to show as well. Or, as Christian Metz puts it, cinema “‘says’ things that could be conveyed also in the language of words; yet it says them differently.”3 Film often suggests rather than shows to immerse viewers, which can occur because we tend to be captivated perceptually and imaginatively to fill the gaps.4 Suggestion can thus be more effective than showing or telling because it calls for a more aware response as it engages our imagination.

In the 1940 adaptation of Rebecca, directed by Hitchcock, Rebecca’s presence from the past is always suggested, whilst she is never shown like it is in the 2020 adaptation. The 1940 version is a great example of how film can engage the imagination of viewers, just as much as a book can. Although Rebecca remains unseen and unheard throughout the 1940 film, Rebecca’s absence creates a presence. How does Hitchcock do this? How does this film shape the viewer’s imaginative visualization of the unseen character?

I expected Rebecca to become visible with every turn of the camera, and although she never did in the 1940 adaptation, in my imagination she was present at almost every moment. This appeal to the imagination was made through numerous visual and verbal cues, one of the most explicit visual cues being the objects left by Rebecca, which are captured onscreen as the new Mrs. De Winter (Joan Fontaine) tries to take in her new position as the lady of Manderley. The new Mrs. De Winter is constantly confronted with her lack as hostess by the R’s embroidered, stitched, and placed on all of Rebecca’s belongings. It is a constant reminder of whom she replaces and who she is being compared to by others.

Both the viewer and Mrs. De Winter learn of Rebecca’s supposedly good reputation through the verbal accounts of others. Even before the ‘I’ of the story becomes Mrs. De Winter, we can hear Mrs. Van Hopper (Florence Bates) talk about them, saying Maxim (Laurence Olivier) “simply adored her”. To the question: “What was Rebecca really like?” Mrs. De Winter (Joan Fontaine) asks Frank Crawley (Reginald Denny) when she is at Manderley, he answers “I suppose she was the most beautiful creature I ever saw...” Through the accounts of Frank, Maxim’s sister Bea, Edith van Hopper and Mrs. Danvers we thus learn that Rebecca was praised for her “breeding, brains and beauty”. Here, it is language that “allows and invites viewers to imagine – in various sensory modes – something that is not shown or heard”.5

This combination of suggestive verbalization and visual cues which appeal to the imagination throughout the 1940 film comes to fruition in the pivotal boathouse scene (big spoilers ahead!), where Maxim confesses the truth about Rebecca’s death to his new wife.

As mentioned before, verbal accounts are one of the film strategies used to suggest. As Maxim recounts what happened in the past, his voice, intonation, and facial expressions are important cues to help our imagination.

In Maxim’s retelling of the night Rebecca died, it becomes apparent how this appeals to the imagination in an even more vivid way. First, through voice and intonation. When the camera tracks Rebecca’s movements (remaining unseen) as Maxim describes them, he uses suggestive verbalization to say what Rebecca said to him as she walked towards him. Using a playful, sinister tone like Rebecca’s, mimicking her words and voice, it conjures up the image of Rebecca.

Then, when the frame of the camera moves to Maxim and he appears in the shot, his facial expressions provide even more ‘food’ for the imagination: He mimics his past emotional expressions as if reliving the moment vividly, and his eye movements suggest presence as they move from one side to the other as Maxim recalls: “She was face to face with me, one hand in her pocket, the other holding a cigarette.” He continues: “She was smiling.” Maxim smiles as well, repeating, mimicking what Rebecca said when she smiled. This adds greater clarity to the imagination of Rebecca’s position, voice, and expression.

At the end of his recalling of events, Maxim reveals how Rebecca fell onto a piece of boat equipment. The door slams into it and makes a sound as the camera tracks down onto the ground. It made the visualization of the fall more vivid to me and it was as if the sound echoed from the memory into the present moment. However, this was not the case, since no acoustic nor visual flashbacks are used. The sound did, however, guide the imagination of the past.

In my experience, this scene created a most vivid imaginative visualization of Rebecca because the image of Rebecca I had built up due to the accounts of her throughout the film became combined in my imagination of her as she walked towards Maxim in the boathouse during his account of the night she died.

Especially through the use of camera movement and the suggestion of Rebecca’s movements, Rebecca seems to rise from the dead as the present becomes past and the past becomes present in this account of the events that transpired between her and Maxim. You see him reliving these moments and we relive them with him through our imagination.

It could be said that the use of suggestive verbalization to do an appeal to the imagination of the spectator is closer to the experience of the book, but the boathouse scene illustrates just how important the actor’s account of the past events is, conjuring up the image of Rebecca through voice, expressions, and eye movements. The filmic device of camera movement brings another dimension to the appeal to the imagination, as it tracks Rebecca’s past movements. Her haunting absence is always present, even from an objective point of view. The film relies on the imagination of the viewer to respond to the suggestions made throughout the film.

“I had listened to his story and part of me went with him like a shadow in his tracks. I too had killed Rebecca, I too had sunk the boat there in the bay. I had listened beside him to the wind and water. I had waited for Mrs. Danvers’ knocking on the door. All this I had suffered with him, all this and more besides.”

- Rebecca, Daphne du Maurier

In the 1940 adaptation, only language and implicit visual cues are used, and no explicit visual illustration comes into play to convey the narrative. It uses suggestion to prompt us to imagine Rebecca, whereas the 2020 adaptation visualizes this subjectivity, making it explicit and forming the spectator’s visualization of Rebecca for them.

The 1940 version asks us to step into the shoes of the new Mrs. de Winter as her anxieties grow and we imagine with her who Rebecca was and what she was like. As spectators, we too seem to have “listened to his story and part of me went with him like a shadow in his tracks.” We imagine Rebecca as Mrs. De Winter imagines Rebecca, and in doing so, create a vivid imaginary account of a character that is never really there, just like our nameless protagonist.

This was such an interesting read, thank you for sharing! 😊 I must put this book on my TBR. 📚

love this!! I agree with you, the 1940 adaptation made an amazing job with keeping the audience engaged!!!